Developing Tak

The Designer with an early prototype, Spring 2015

Tak: The Origins of a Modern Classic

In his best-selling 2011 fantasy novel The Wise Man’s Fear, Patrick Rothfuss described an abstract game called Tak. With echoes of classic games like chess and go, Tak was challenging and timeless, a favorite pastime of the world’s most discerning players.

Three years later, Patrick gave me the opportunity to develop his idea into a real game. This post tells the origin story of Tak: a Beautiful Game.

Setting the Scene

In 2014, Patrick Rothfuss helped me out with a new card game called Pairs. That game wasn’t from his books, but we agreed that his world would be a good match for the game. During that project, I offered to write a set of rules for Tak. Patrick and I made it official as a stretch goal in the Pairs Kickstarter campaign.

A few months later, Patrick sat down with me to talk through everything he knew about Tak. Not just what he wrote in the book, but everything that he wanted this game to be. With Patrick’s description in hand, I embarked on the project in December 2014. Eight weeks later, I was nervously showing Patrick a first demo of his ancient fictional game.

Patrick was wise in the book, including almost no specifics about the game rules. He wrote of its elegance and beauty, but in loose terms that could describe nearly any abstract game. As a gamer himself, Patrick knew that any mention of actual mechanics, even as little as “I won the game in ten moves,” could paint him into a corner if he ever tried to create a real game. This made it easy for me to start the project with a clean slate.

Early Drafts

The mechanics of Tak took shape in December 2014 and January 2015. I started with Patrick’s basic concepts, and the world of The Wise Man’s Fear, along with what I knew about abstract games in general.

Patrick described several mechanical elements in his original concept, some of which didn’t make the final cut. In broad strokes, the game was a “classic abstract,” meaning it was played with simple pieces and rules. There should be no writing, no language elements, no complexities beyond what one might find in chess or backgammon.

As written, the game is played with a board and several pieces called “stones,” perhaps similar to chess or go. Furthermore, as Patrick explained to me, Tak stones could be stacked up, sometimes in an unwieldy pile, and each player might have their own specific assortment of stones.

Patrick suggested the idea of simple pieces that could stack up and gain or combine powers. He also liked the idea of road building, if it could be included as some kind of mechanic or story element. He wasn’t sure if roads should represent conduits for power, avenues for piece movement, or something else. This idea eventually became the core victory condition.

Patrick’s concept also had a dexterity element. Stones might be easy or hard to stack, and dealing with toppled stacks was a part of the meta-game. (Play ‘em where they land!) Each player could develop a feel for the quirks of their own personal set, and a player’s dexterity and knowledge of their own pieces could provide an advantage.

While writing the book, Pat tried to design a version of Tak, though he didn’t show me those rules until much later. His version was an area control game where stones were played in stacks, to exert influence on neighboring spaces. Later, he explained that his game never worked as intended, because no matter what each player did, it always ended in a tie!

First Playable

Prior to receiving Patrick’s notes, I’d been thinking for months about what defines a classic abstract, and how I might create a new one. As a baseline, a game in this category should have a fairly short play time, and should be easily accessible to new players, while also providing plenty of depth for experts. (Per the famous Othello slogan.) Yes, this is easier said than done, but it’s still a goal.

A classic abstract game might have a random element (as in backgammon), or it could be pure strategy (as in chess). The pieces should be simple, and the game should be language-neutral. It should be something you could create with basic materials and tools.

I read the books again in depth, because I’m a story-first game designer at heart, and I wanted to make sure that Tak felt like a true artifact of Patrick’s world. I didn’t just focus on the passages where the game appears. I needed to be ready to draw from anything.

From this foundation, and my conversations with Patrick, I quickly suggested the mission statement “Tak is a beautiful game.” This core goal eventually became the game’s official subtitle, and it informed every aspect from the mechanics to the packaging.

From my reading, the game was pure strategy. This didn’t fit with any randomizer, including dexterity elements, so I was leery of including the Jenga-like elements of Patrick’s concept. Also, I’d already had some experience blending dexterity and strategy games, which taught me that the hybrid game appeals only to those few people who like both parts. (Darts plus miniatures equals Diceland, which is fun, but not my best-selling game.) So I convinced Patrick to abandon the toppling stacks, in favor of a purely abstract game.

However, the notion of each player fine-tuning their set, though a fairly modern concept, was still interesting enough to try out. More on that a bit later.

The idea of stacking pieces to make more powerful pieces was very interesting. I think every game designer comes up with some variant of “stacking chess” at some point, a game in which basic pieces can fuse together and consolidate powers, such as a rook and a bishop combining to make a queen. However, I knew that even a few combinations of powers could make a game far too complex.

I’d recently created a game called Veritas, with Mike Selinker, in which players build and move stacks of simple pieces. This is an ancient mechanic drawn from mancala, by way of Devil Bunny Hates the Earth. I thought some version of stack-and-move might be a good foundation for Tak, especially with Patrick’s thoughts about stacking pieces.

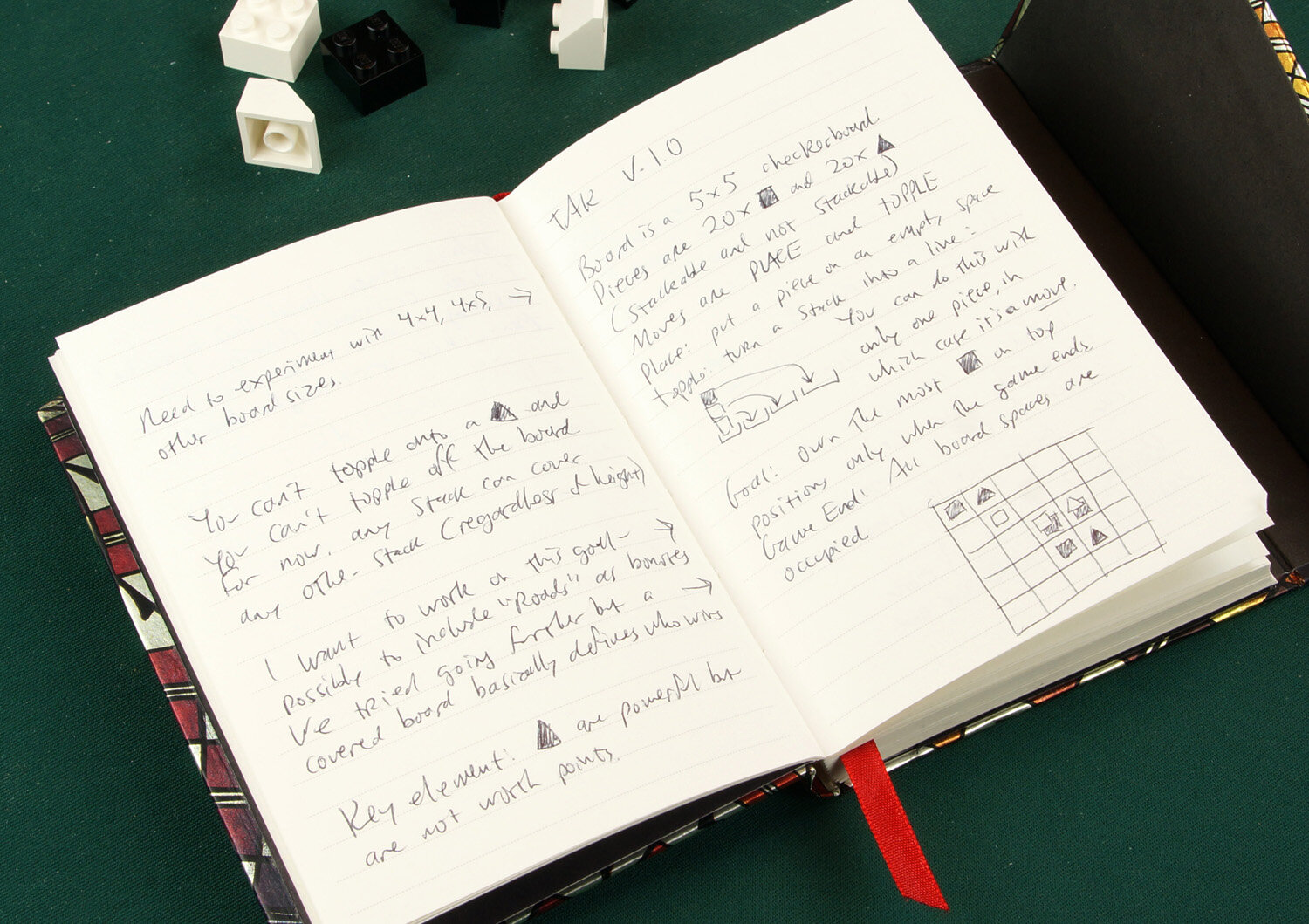

The first basic rule was that a stack moved Veritas-style, dropping exactly one piece from the bottom onto each space it moves through. I introduced a second type of stone, which could not be covered by another piece, and therefore could only be played as the top part of a stack. They were called “sharp” and “flat” stones, represented in this notebook sketch by triangles and squares.

Early Tak notes, December 2014

With two types of stone, I thought perhaps a player might fine-tune his own set of pieces to include any mix of flat and pointed stones. I built a set of Lego pieces and experimented with “tuning” a piece set that was a varied mix of sharp and flat stones.

Ultimately, I realized that the ideal stone piece was a single shape that could be played either flat or standing. This change removed the possibility for players to construct their own set. But to me, this set-tuning mechanic had always felt a little too modern, rather like a solution looking for a problem, and I think the game is better without it. In this context, I don’t really want to play the game before I play the game.

The notion of “flat” and “standing” stones is an echo from the world of the books, where mysterious megaliths pepper the countryside, and are found in both upright and fallen states.

The first objective was area control, although as you can see above, roads were always intended to be good for something. The combination of territory control and roads was based loosely on Veritas and similar games, including two earlier other games of mine called Land Rush, and Queensland. In these games, the board starts blank (or mostly blank), and players add and move pieces throughout the game.

Early Development

As with Patrick’s early attempts, my first games of Tak tended to end in a tie. Not always, but more often than I liked. One solution was to play the game on a 5x5 board, which had an odd number of spaces (the game was over when the board was full). But I was still fiddling with the size of the board, and I liked the fact that the game of go could be played on different sizes of board for different levels of challenge. If I wanted to include 4x4 and 6x6 boards, I’d have to look for a solution that led to fewer ties.

One early rule was that standing stones did not count for points, so they were used mostly as blockers and to control tall stacks. Unfortunately, this led to lower scores, and an even higher chance of a tied game, and the game as a whole still wasn’t very interesting.

I decided to incorporate the roads as a victory condition, similar to Land Rush or the Alex Randolph game Twixt. This change made the game faster, and led to earlier excitement with threats and countermeasures possible long before the board was close to full. The original territory win remained as a tiebreaker for games that finish without a road.

Even after the addition of roads, the game still seemed a little “flat.” Also, standing stones seemed a bit too powerful, even when they could not count as part of a road. To add wrinkles to the game, I decided to incorporate a new piece, the capstone, which had the best parts of both standing stones (can’t be covered) and flat stones (can be part of a road), along with a new ability, which is to flatten standing stones. It’s a powerful piece, but limited by being unique.

When I say the game seemed “flat,” I mean there was low variability in the game space, or in other words that there weren’t enough different ways that a game could play out. The trick in designing any game in this space is to create a simple set of rules that can give rise to many meaningfully different games and game states. This means that each mechanic should add a new dimension to the game. “Wrinkles” is my shorthand for places in the game flow that feel different in an interesting way. The capstone adds wrinkles.

The core design challenge became the definition of “move,” the fundamental mechanic of the game. Can a stack drop more than one piece at a time? Can it turn corners, or must it travel in a straight line? How many pieces can move at once? What happens when I hit the edge of the board? And so on.

If a stack must drop exactly one piece at a time, movement becomes too limited and is hard to use effectively. But if a stack can turn corners, it’s too open, and thus too hard to predict, which makes it harder for either player to look very far ahead. And so on. We found the best mix of rules after iterating and experimenting with a clear goal in mind.

The rules of stacking and movement satisfied the design goal that simple pieces can combine into a more powerful “piece” (more precisely, a more powerful turn). These specific stacking rules added the wrinkle (familiar from Veritas) that a stack often contains enemy pieces.

All of these changes transpired in just a few weeks. Roads as a victory condition happened on day three, more or less. Many rules died fast and never even made it into the notebook. This might seem like a lot of changes in a short time, but this is what early days are like. As you can see from this breakdown, I was drawing on my experience with related games, trying to bring the best parts together into something new.

Also, I had a deadline.

First Pitch

I showed Patrick the first playable version of Tak in the first week of February of 2015, while we were sailing on the JoCo Cruise. As he tells it, Patrick had been steeling himself for weeks to reject the game gracefully, without losing me as a friend. He overlooked two key elements of this process: first, that I can take criticism pretty well; and second, that the game might actually be good.

After the first couple of plays, he shook his head and declared that we had nailed it. From there we were off to the races, into a phase of development that would broaden the pool of testers and last another year.

Right away, Patrick’s friends put the game through the same trials as my own test groups had done: looking for holes in the rules, trying to exploit various degenerate strategies, and finding themselves more or less unable to break it.

For example, one player leaned into the “always play walls” strategy, arguing that standing stones were too strong, and playing every stone standing. After losing on the flats, he played only half the stones standing, then only a third, and so on, eventually admitting that playing just a few standing stones was his “broken” strategy, at which point we agreed he was simply playing the game as intended.

Advanced Development

Even with the rules mostly in hand, many questions still remained about the best way to market this game. What material should we use for the pieces? Should we share the rules for free? Can we sell a piece set without a board? What does the core product look like, and who will publish it?

In the beginning, it wasn’t certain that Cheapass Games would be the publisher, as we were not exactly known for games of this category. Patrick and I entertained some offers from other publishers, but in the end we decided to release it through Cheapass Games, but without the Cheapass logo. Strangely, some reviewers still derided the Cheapass logo on the box, even though it wasn’t there. Some brands apparently transcend redaction.

I set up a wood shop to make prototypes, testing piece sizes and shapes. For months, I carried a small bag of pieces everywhere I went, playing pickup games without a board to determine whether it was practical. As it turned out, the no-board game was perfectly playable and much more portable. I imagine that a traveler in a fantasy setting would be happier to carry just a bag of pieces.

With Patrick’s blessing, I released the rules to the public in the fall of 2015. In an instant, an army of Rothfuss fans began playing the game, making their own sets, and building digital versions to help us crack the game and fix corner cases in the rules. What happens when two players win at the same time? What does that even mean? Thanks to those programmers, we now have the answer.

Those simulations also pointed up something we already knew, which was that this game tends to favor the first player. At least in those early games, first players were winning about 55% of the games. I had anticipated this, because almost no turn-based abstract game can be perfectly balanced for both players. My solution was to include a scoring system, awarding more points to players who win with fewer pieces. In this way, players can play two games (each starting once) and add their scores for a perfectly fair game.

Players suggested (and continue to suggest) changes to the rules and the setup so that a single game can be perfectly balanced, but I don’t think will ever be a perfect answer. This challenge sticks in the craw of tournament players, who don’t like dealing with cases when the two-game score is tied. But as far as I’m concerned, that’s another solution looking for a problem, and I think that in the spirit of classic games, Tak already has all the rules it needs.

And Then Some

The Tak Kickstarter campaign ran in the spring of 2016 and raised $1.35M. Some of that money even stayed in my pocket, though I promise you that printing and shipping 12,000 board games isn’t cheap.

We used the best materials we could: real wooden pieces, manufactured in the US, with gorgeous art by Echo Chernik and Nate Taylor. We partnered with Wyrmwood Gaming to produce some incredible high-end sets for the more discerning fans. And Patrick and I wrote a detailed history of the game, along with rules for a few “previous” games, which we published as the Tak Companion Book.

The game has been well received. As of 2021 it’s in its third edition, now with Greater Than Games. It has stellar reviews on Amazon and Boardgamegeek, where it’s currently ranked #20 in the abstract games category. Tak was nominated for an Origins Award, and it seems on track to become the world’s favorite game in roughly sixty thousand years, shortly after the Earth is overrun by mechanical bees.

Credit is due to my early-round playtesters, who helped the game come together in record time: Boyan Radakovich, Paul Peterson, Rick Fish, Jeff Morrow, Jeff Wilcox, and Joe Kisenwether. And of course to Patrick Rothfuss, who set the stage for all of this.

Let’s do it again sometime.

Stones and Capstones from a unique three-color set (really, three sets), made by James Ernest for Paul Peterson